Note: this article is aimed towards musicians with at least a basic understanding of reading sheet music, but those without this can skip the sheet music examples/terminology and still appreciate the overall discussion.

Why do we care about quality in our daily lives? What does a quality product mean, and how does its quality affect its user?

Here at Bollypiano, we consider those questions when designing quality sheet music arrangements of South Asian pop music for the player. Bollypiano operates under four central principles, which we can memorize as the acronym PAPA. Sheet music should be:

- Professional – notated and formatted to music industry standards.

- Accurate – transcribed and arranged such that the melodies and chords in the sheet music closely* (subjective term discussed later) match the original song. Note: this only applies to transcriptions and arrangements, not original compositions

- Playable – natural to play for whatever instrument it’s designed for.

- Affordable – financially accessible to a large audience of people around the world, reflective of the global nature of South Asian culture and its diasporas. This point is not relevant to this article.

This article carefully describes how Bollypiano approaches quality with the first three principles in designing its sheet music products, with the hope that it can provide helpful advice for any aspiring amateur or professional musician/composer in the world looking to design their own quality sheet music for any purpose.

Professional

Notated and formatted to music industry standards

Unfortunately, there does not seem to be a definitive list of standards that the “music industry” considers professional easily searchable on the Internet. A cursory search using sheet music industry standards from the UK reveals the following four search results:

- “Sheet music – Wikipedia” – no doubt a fantastic article on what sheet music is

- “Understanding Split and Lyric Sheets – Songtrust Blog” – advice to songwriters on how to design a special type of sheet music

- “How Does Music Publishing Work?” – don’t worry about this just yet, but this is not related

- “Music Industry Guide – The British Library” – advice on how to navigate the music industry

Fortunately, the eighth search result links to a question posted on https://music.stackexchange.com asking the very same question we are asking, with a reasonable answer. The accepted answer recommends reading the book Behind Bars: The Definitive Guide to Music Notation by Elaine Gould, which itself only concerns notation (to be fair it is a very deep topic already). However, if you don’t want to go off and read an entire book, the above illustrates how hard it is to find definitive standards for notating and formatting sheet music.

There are other ways to learn, such as through music education and years of training in music composition, but Bollypiano does not make the assumption here that you, dear reader, necessarily have that benefit or time. Therefore, we have chosen to set our own “Bollypiano standards” in terms of what makes a sheet music “professional”, using our own music experience, training, and what other established sheet music platforms use. Before we go in-depth describing what “professional” means, let’s summarise it as generally as possible.

Bollypiano considers sheet music “professional” when it is:

- Made using music notation software (with the benefit of automatic notation/formatting it provides)

- Notated through pitches and durations in a context, in such a way that any musician can easily and quickly understand, play, and feel the music

- Formatted to clearly 1) convey the structure of the song; 2) give every symbol (note, signature, accidental, etc.) enough space for readability; 3) inform the reader about the song title, songwriters, and any other relevant song metadata

Professional Notation

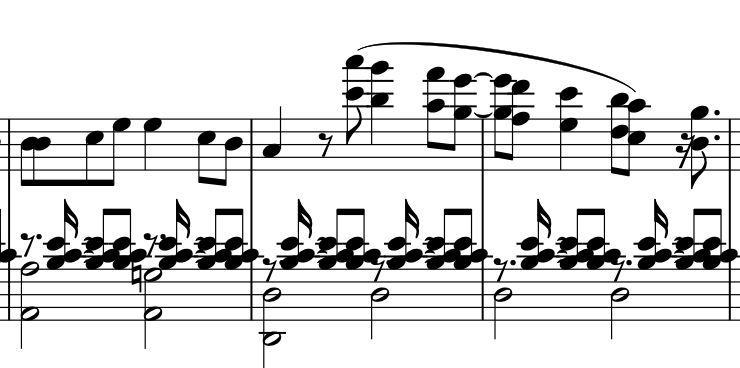

Bollypiano follows western music notation as the standard for notating our sheet music. For those learning music notation, we encourage using music notation software (Bollypiano uses Sibelius, but MuseScore is a suitable free alternative) as they automatically help you format notation to make sure your notes’ durations make sense (how they look is a different matter), as well as other helpful automatic formatting. To understand what separates “professional” and “un-professional” music notation, we must start from the basic ideas of music notation. The core idea, at least for Bollypiano’s purposes, is this: music notation is a system which represents the pitch and duration of any instance of sound within its larger context. Let’s look at a sheet music example below.

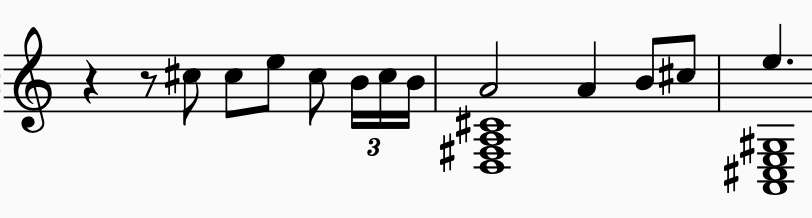

We can see the Note which is an instance of sound – it is produced, it “happens”, and is on the sheet music. It has a pitch“A” (or more technically, “A above middle C” or “A4”) which represents its sound frequency 440 Hz (Hertz), and a duration “half” (US) / “minim” (UK) which represents how long the sound happens for (relative to the tempo marking of “126 bpm”). A note’s pitch and duration displayed on the sheet are affected by its larger context, represented by the red boxes. This larger context describes how the note’s pitch and duration on the sheet music really sound in the real world. The “larger context” is itself a deep and broad topic (who knew there was so much to music notation?!).

Our discussion so far has alluded to the idea that music notation (and sheet music in general) is a representation of real world sounds. There are technically an infinite amount of ways one can represent a song in music notation, but there is always a small number of best ways to do it. By “best”, we mean that, like a set of instructions for a tool, the notation is easily and quickly understandable to any musician who can read sheet music.

Using the example again from earlier, imagine being given the notation below instead of the first Naina Da Kya Kasoor example to play.

The pitches and durations are there, but there is less context. How fast do we play this? What time signature/meter drives the rhythm of the song? Without a key signature, do we have to put up with repeating sharps/flats throughout the whole sheet? What notes do I play in the left hand? There are many worse examples on the Internet!

Below, we outline general aspects of pitch, duration, and context to keep in mind when notating sheet music “professionally” which music notation software won’t catch (as mentioned their usage is highly recommended). Music notation terminology will be used below.

Pitches

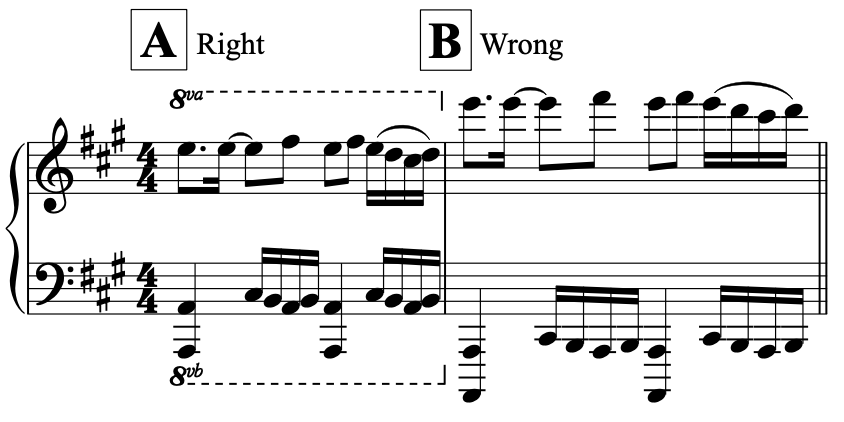

- Notes, particularly in the treble clef, are notated on the staves as much as possible without the use of ledger lines – more leeway can be given to left-hand notes if they are part of octaves (the higher note in the octave is more readable, so the reader can assume the lower note is the same note but an octave lower)

- Pitches are separated by staves corresponding to how sheet music is written for a particular instrument. For example, piano music almost always has two staves, while violin music always has one staff

- Be aware of what key signature is in use, and notate accidentals accordingly. As a rule of thumb: key signatures with sharps translate to sharp accidentals, and those with flats translate to flat accidentals; exceptions to these cases involve chromatic note movement, in which case use the accidental which follows the up- or down- step (sharp for upwards movement, flat for downwards movement)

Durations

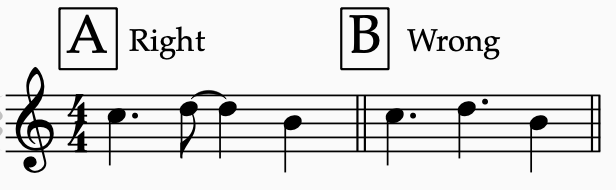

- Consider where to tie held notes together given the time signature/meter, for meter/rhythm readability

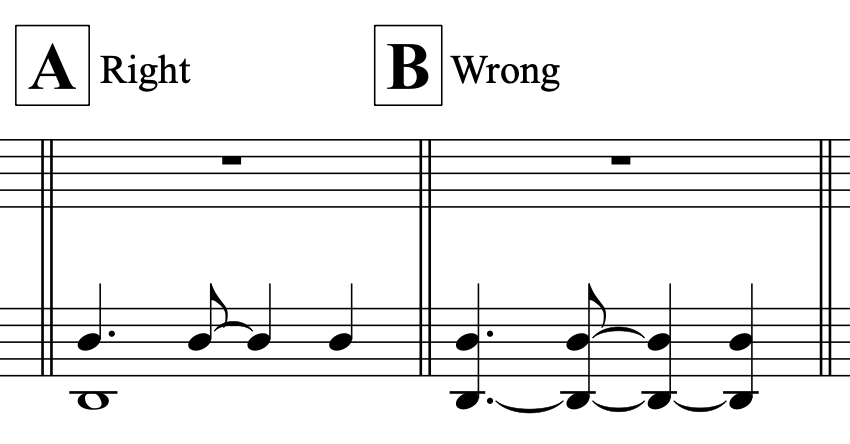

- If there is more than one melody line happening at the same time, use different “voices” to represent them. This can be found in any music notation software’s “voices” functionality

- For the same note instance (tied over multiple notes) or same silence happening over a period of time, consider simplifying how it is displayed on the page by grouping the tied notes or rests together into less symbols. For example, oftentimes we can display a single half/minim rest instead of two quarter/crotchet rests, because it is easier to read

Context

The following aspects should be present:

- Tempo marking

- Clefs – usually treble and bass for piano sheet music, but ultimately depend on which range (low/middle/high) of the keyboard the player’s hands are in at that time

- Time signature – one which matches the beat/rhythm of the song and neatly groups notes together per beat

- Key signature – one which necessitates the least number of accidentals throughout the sheet; this includes modal key signatures (a song notated in E minor but containing a lot of C#s should be considered E Dorian, therefore it should use a key signature containing C# like F# minor)

- Expression/dynamics markings – how soft or loud should the song be played? Use Italian piano/forte dynamic markings, as is standard in Western sheet music, as well as “hairpins” to indicate the sound level getting softer or louder

Professional Formatting

Thankfully, our discussion on formatting will be less music terminology-heavy than the one on notation. As with notation, the “professional” sheet music creator must remember the principle of designing easy-to-read sheet music when formatting their sheet music. For Bollypiano, “formatting” entails a few aspects which will be discussed below.

Song Structure

Almost every song in existence has some kind of structure, and a good sheet music representation of a song shows that structure in some way – usually through double bar-lines, special indications of section-wide repeats (D.S. al coda, etc.), and/or splitting staff systems like a coda section.

Symbol Readability

Symbols (notes, accidentals, etc.) should not overlap each other or look squished onto the page. Music notation software may or may not have tools to prevent this – Sibelius’s has the “magnetic layout” tool for this problem, for example, but these tools will not detect all “collisions” like this. Forcing too many bars onto a single staff system also causes these problems, as well as forcing too many staff systems onto a single page. You may need to look over your sheet with your own eyes at the end of your work to check for any collisions after enforcing these tools.

Song Metadata

The term “metadata” is rather technical, but it simply means information that adds context to the product, whatever it is! In this case, sheet music metadata includes:

- Song title

- Song subtitle (optional) – if it comes from a movie, if the sheet is for a specific instrument, if the music has been transposed from the original song recording key signature, etc.

- Songwriter/composer – music & lyrics credits for the original song (if the sheet is an arrangement or transcription), and a composer/arranger credit for you

- Copyright – usually found at the bottom of the first page. If the sheet is an arrangement or transcription, include the original copyright holder. In any case, include your own as well. Music copyright itself is a large and complicated topic which this article will not go into!

Accurate

Melodies and chords closely resemble the original song

As noted in the introduction, this section only concerns arrangements and transcriptions, not original compositions. We must first start with some general definitions:

- Arrangement – a musical work derived from an original composition, transformed into its own composition (it could also mean extra instrument parts added to a song by a music writer who is not the original composer, but is not relevant here)

- Transcription – a record or representation of any piece of music to convey what is originally heard

Bollypiano deals exclusively with both types of work defined above, and has a particular approach to arrangements with respect to their representation of the original song. It should be made clear that standalone arrangements, by definition, have no requirement to be strictly accurate (in terms of melodies, chords, even chord progressions, etc.) compared to the original song. A composer of an arrangement has artistic license to write whatever they want in it. But what makes an arrangement effective is for an audience familiar with the original song to recognise it from the arrangement. Therefore, there needs to be some accuracy and resemblance to the original song when it comes to an arrangement. In Bollypiano’s case, we have chosen to arrange piano music with a target of >99% accuracy with respect to the original song’s melodies, chords, and chord progressions, with some leeway on whether to include lengthy instrumentals/interludes or not (we assume the player is satisfied with playing the main sections of the song).

If an arranger has trouble trying to produce an “accurate” arrangement with this definition, they can try the following:

- Verify whether each chord in the arrangement is in the correct mode (major or minor)

- Attempt to include as many notes from the original chord in the arranged chord as possible; for example, the original chord is a complicated C minor 7th with added 11th (C, Eb, G, Bb, F), but the arranger should at least extract/arrange a C minor chord (C, Eb, G)

- Listen to and record what the bass in the original song recording is playing – it is often one of the best indicators of what the chord is at that moment

These points hint at the fact that musical aural skills are of the highest importance for any arranger/composer!

Transcriptions are meant to be accurate representations of the original song. They could cover the entire song, or they could cover a famous instrumental solo (as is found sometimes in jazz transcriptions). A common name for transcriptions which accurately capture the melody, chords, and lyrics of a song is a “lead sheet”. At Bollypiano, we go the extra step with lead sheets by annotating the most important instruments that can be heard in the original song recording (although this may be subject to change depending on what our customers want!).

Bollypiano considers sheet music “accurate” when:

- Any listener can easily recognise the original song, guaranteed by adhering to a standard of at least 99% accuracy for all melodies, chords, and chord progressions

- Both arrangements and transcriptions follow the rule above

Playable

Natural to play on the instrument written for

Humans naturally have physical limitations when playing an instrument. Assuming no physical injuries or impediments, a pianist has ten fingers on two hands to press the piano keys with. Beyond that, the discussion on physical limitations with these ten fingers in piano music gets tricky, because it is difficult to explain exactly what piano music is “playable” and what isn’t without accounting for all variations in human physiology. What a composer/arranger can do to verify whether their work is “playable” for a given instrument they’re writing for is:

- Play the sheet music themselves – this is often the quickest way to identifying playability issues

- Ask any player of that instrument they know to read and play the composer’s sheet music, then receive feedback on how to modify the written music to be more playable

- Consult an orchestration guide – these are designed primarily for orchestral composers, but provide general tips as to what to do or avoid when writing for a particular instrument in the guide

Another aspect of playability is whether the music written by the composer is too physically high or low for the instrument itself. A convenient tool to check this is simply to use music notation software, which would give some indication/warning on whether a note is outside of the physically playable range. However, the success of this is dependent on whether the composer is writing for the intended instrument in the software or not – a mistakenly low note not playable on the violin will not be caught if the instrument written for is the piano, for example.

Bollypiano considers sheet music “playable” when:

- A player/musician of the instrument written for can physically comfortably play it, without awkward/challenging movements in the hands (or any other body parts!)

Summary

Writing sheet music, let alone quality sheet music, can be challenging and require years of experience and training. In summary, creating quality sheet music by Bollypiano’s standards entails the following:

- Notate and format sheet music which is easily and quickly understandable to any musician

- For effective arrangements, consider what level of accuracy is important enough for your purpose

- Make sure your sheet music is naturally playable by getting yourself or someone else to play it

- Use music notation software

Thank you for reading, and go forth and create beautiful sheet music!